Building Blade Runner 2049

VFX Studio Double Negative on Creating a Dystopian Future LA

Being tasked with creating a vision of future LA isn’t easy, but being asked to build a vision of future LA that also pays homage to a seminal movie is near impossible. That was the situation VFX studio Double Negative found itself in, but now Blade Runner 2049 has been rewarded with an Academy Award for visual effects, we hear how the studio built a version of LA fit for the mid-21st century

Having been introduced to the neon-dystopian world of Blade Runner in Ridley Scott’s original 1982 movie, last autumn saw an expanded and more vivid version of near-future Los Angeles come to the big screen in Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049.

Charged with taking the original interpretation and fast forwarding it was the VFX studio Double Negative.

The studio was responsible for most of the Los Angeles 2049 cityscapes, the Joi hologram effects and the seawall chase at the end of the movie, which was all work that contributed to Blade Runner 2049 winning an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects.

To celebrate its win, we hear from Graham Jack, Double Negative’s chief technology officer, on how he and his team went about scaling up the world of Blade Runner, and in the process invented a world that pays homage its inspiration, but still shows the audience that time has passed, and time hasn’t been kind to this world.

"We wanted to do justice to the original, but at the same time when we looked at dystopian cityscapes in movies since Blade Runner they all kind of leant heavily on the original and we really wanted to do something different.

"We wanted to feel like we were seeing an expanded world from the original movie, but we didn't want it to feel just like a copy of Blade Runner. So we needed to develop some different ideas, and we started to think about how to do that and the key thing really was to create something believable.

"In visual effects these days you can pretty much make anything, but if you want to make it something the audience will believe in and engage with, it needs to have some sort of grounding in perceived reality. And so we set out to find what the story and the logic was that would make the world look the way it did."

"The thing we came up with was if you think of the original movie the sequel is set 30 years later and the idea is that the climate has continued to deteriorate. We're looking at a world that's broken. Humanity has broken this world. And so that's kind of the story that we were trying to develop and we were trying to think how does that story affect things like the architecture and the design of the city.

"We went and we looked in a bunch of reference images of the real world of kind of polluted cityscapes. And we settled on a lot of images coming from China as well as these kind of hazy polluted atmospheres. The other thing that we were inspired by was some of the Monumentalist architecture that we're starting to see popping up in modern China."

“We ended up with something that the director really liked. It kind of has this cold feel, like L.A. has become this cold fog drenched snowy landscape and that you know it really feels like a world is dying. So, from there when the shoot finished we had to try and figure out how we were going to translate that into what we see in the movie.”

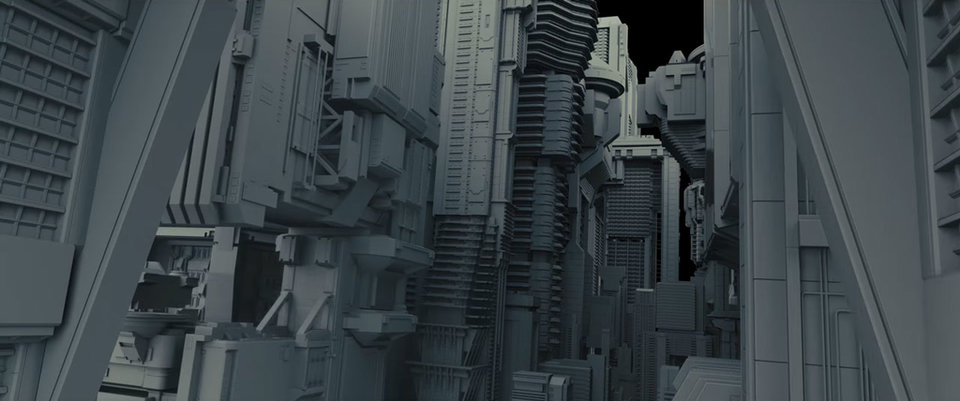

“You can see this is quite a lot of complexity in there. A lot of, a lot of buildings, and then on top of those building there's an extra detail coming in that gives you things like fire escapes, air conditioning vents and things like that. Even though when you get to the final shot a lot of it is lost in the fog and the darkness. We wanted to make sure that we kind of retained a very realistic and gritty image and that meant that even though it's almost imperceptible that detail still had to be there.”

“All the detail kind of gives us a problem, which is basically a data problem. So we have these huge data sets, we have you know hundreds of buildings on screen and each of those buildings is made up of hundreds of components. Even before you start covering it and all of the additional detail that we need to make it look real.

"In some scenes most of the shots had upward of nine-hundred-billion individual polygons in the scene at any one time. And we have to turn that 3D data into the final images; it's a process that we call rendering, and it's a very computationally intensive task. We have a data centre with thousands of blade servers all pulling data from our storage in order to be able to compute these final frames.

"Somebody said that visual effects rendering essentially amounts to a 24-7 denial of service attack on your network infrastructure. So dealing with how you get all that data off our storage and onto that onto the screen that was probably our biggest challenge.”

"You know I think it's interesting to think about when we get to 2049 what's the world going to look like what's technology going to look like I hope it's not going to be as bleak as the movie makes out.

"I'm going to leave you just with a little reel showing some of the other work that we completed on the movie."